Comment:

This is a paper I wrote for a course on procurements and included in my series Supply Chain Basics. If you have followed my blog posts you may have realized that I am a proponent of complex adaptive systems (CAS). I have found that CAS reflects natural relationships such that organizational latency is reduced, collaboration and information sharing increase, and problem-solving occurs at the point of origin. The business or operation must be properly structured in order to take advantage of CAS. Once again, I have applied this concept to complex projects and procurements.

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges in project management is complexity which is common to mega-projects but also common to smaller highly integrated projects. Complexity occurs in many dynamic forms such as in scalability, relationships, the tempo of the project, and due to self-organization. Complexity affects project procurement costs due to uncertainty in quantity and timing. In some cases, the actual procurements required remains in question until conditions emerge such that a determination can be made as in progressive elaboration events. The greater challenge is not the actual procurements but instead the management of or adaptability to emergent conditions while maintaining optimal procurements otherwise known as innovative procurements or simply innovation. In complex projects, the project procurement practices of the plan, conduct, administer, and closeout fall short of providing the requisite level of management. How does a project manager design and implement procurement systems or programs that assure optimal procurement processes in the face of uncertainty driven by complexity?

Clarifying Project Complexity

A formal definition of mega-projects does not exist among scholars but the United States government defines mega-projects as major infrastructure projects exceeding $500US million or projects that attract a high level of public or political attention due to impacts on the community, environment, or budgets (Li, Yanfei, and Chaosheng, 2009). Regardless of the definition or whether a highly integrated or mega-project, complexity is present and best described as projects that have a high degree of uncertainty and dynamic relationships among the participants. A closer look at complexity reveals the nature of the project culture. Scalability relates to sizing or the scale of the effort indicating the type of management and controls. Relationships among the participants such as serial, parallel, or nonlinear indicates the participant’s collaborative interest and willingness to cooperate. Self-organization traits of the project participants relate to the ability to adapt to emergent conditions in order to learn and solve problems. The project tempo relates to the rapidity with which decisions must be made and the effort progresses. Projects operating under a compressed timeline must make reliable decisions sooner than projects under normal time constraints. Optimal procurement processes are adaptive to the emergent conditions, minimize overall legal claims, promote quality, and correctly specify materials and services. The project manager must bring these objectives into succinct focus while managing complex projects.

Procurement Planning

Many managers are realizing that the control of overall complexity is a strategic issue for the company (Isk, 2010, pp. 3681-3682). The process begins before the scoping and work breakdown structure is considered by surveying the ground conditions such as the form of complexity, anticipated project tempo, and the nature of the expected procurements in order to begin formulation of the management method.

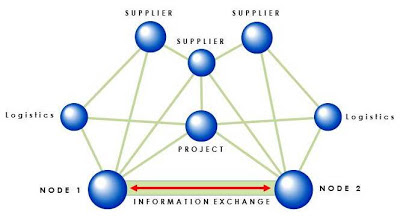

Project managers reel over uncertainty and the lack of structure. Complexity is typically wrought with uncertainty causing project managers an uneasy sensibility. Somehow, project managers must apply structure to complex projects in order to stabilize the core focus areas and, in particular, the project procurements. Complex environments rely on several key activities; information sharing, transparency, communications, and autonomy. These activities are necessary for the project participants operating under complex circumstances to adapt to emergent conditions otherwise known as the ability to innovate. Complex adaptive systems are the structure of complex environments that can facilitate key activities. Complex adaptive systems, Figure 1, are composed of autonomous nodes and communication pipes between the nodes reflecting a molecular lattice. In this case, the autonomous nodes represent suppliers, work centers, stakeholders, and other project participants. The communication pipes between the nodes pass Information Exchange Requirements, IERs, over the pipes and possess the self-organizing capability of dynamically connecting and disconnecting from nodes as necessary. With this architecture in mind, project managers can begin to overlay policies and practices to manage the complex environment. "Owing to the inherent complexity, it is a challenge to coordinate the actions of entities across organizational boundaries so that they perform in a coherent manner (Surana, A., Kumara, S., Greaves, M., & Raghavan, U. 2005, p. 4241)."

Figure 1: Complex Adaptive Systems exchange information and self-organize

Supply Networks

Supply networks can be ‘dyadic’ to multi-firm groupings (Brady, 2011). The variety and uncertainty of a supply chain might be extremely high and cause complexity. A typical supply chain can often be complex as a large mesh having members with competing objectives in other supply chains that dynamically reform (Isik, 2010, p.3685). At the most basic level, supply networks vary in structure based on the predictability of demand and complexity of the finished goods. Regardless of the supply network’s detail, the complex adaptive construct can be mapped to it. The greatest concern for a project manager is the supply network’s ability to be responsive and solve problems autonomously or to be innovative. Supplier competitive and self-interest factors detract from the desirable traits of collaboration and innovation. The project manager must put all the traits into balance in order to keep cost low and innovation high.

The more complex, high technology, and high cost the product becomes the more significant systems integration becomes the productive activity of the organization (Brady, 2011, p. 471). Complex adaptive constructs combined with program management provide such integration through teaming.

Procurement Management Program

Cost overruns of 50% are common; overruns of 100% are not uncommon. Project management is of enormous value to the success of mega-projects (Li, Yanfei, and Chaosheng, 2009, p. 100). The source of the cost overruns is uncertainty or risk. There are five main sources of risk; (1) Lack of buyer understanding of the requirements, (2) Language shortcomings, (3) Behavior of the parties, (4) Haste, and (5) Deception (Garrett, 2010, p. 50).

A procurement management program frames and provides guidance in order to address risk factors and strengthen the project procurement process such that cost overruns are reduced to acceptable levels. The underpinnings of a procurement program can be addressed in a structured manner the complex adaptive systems as the underpinnings. As indicated prior, optimal procurement processes are innovative and adaptive to the emergent conditions, minimize litigations or claims in the end, promote quality, and correctly specify materials and services. The objective of managing procurements in this manner is to derive value for the project.

The British Airport Authority was confronted with supplier conflict, poor information sharing, unwillingness to accept risk, and the lack of a consistent process among other issues. The solution embodied two main principles; the client always bears the risk and the work was to be carried out by integrated project teams. The British Airport Authority took on the role replacing the lead firm as systems integrator creating a framework of agreements that led to a value-creating supplier network (Brady, 2011, pp. 475-479).

The centerpiece of a program is the type of contracts and agreements made between the contractors or suppliers that leverage the complex adaptive systems traits. These agreements may be viewed as a teaming arrangement which is an agreement between two or more firms to form an alliance for their mutual benefit in a project (Fleming, 2003, pp. 36-37).

A system of agreements should be developed as part of the procurement management program that frame the level of collaboration and empowerment in a way to reduce destructive competition or conflict, properly assign risk, and solve procurement problems as they emerge. This was a success in the Heathrow terminal project where the approach consisted of four main components in the agreement; a single model environment, the use of preassembly, prefabrication, off-site testing, and just-in-time logistics (Brady, 2011, p. 477). One agreement should frame the project procurement structure as did the Heathrow project. Another agreement should frame guidance for cross-functional teams that strengthen collaboration, information sharing, and problem-solving. This approach was a success in the SHRBC construction project where long term strategic cooperative partnerships yielded a high satisfaction with collaboration and looked forward to future cooperation projects (Li, Yanfei, and Chaosheng, 2009, p. 107). Other agreements with the procurement participants can be developed on an as-needed basis. Once the framework for the procurement program is in place then the project procurement practices of the plan, conduct, administer, and closeout, can be integrated into the overall management effort.

The project procurement practices will follow the Project Management Institutes model as closely as possible. This involves the Request for Information, Request for Quotes, and Request for Proposals as well as contract type selections. The procurement management program could have agreements that provide guidance to the participants in the procurement process regarding the project procurement practices in these areas. For example, several contract types could be utilized during the project in a strategic manner. Cost-plus and fixed fees could be used to reduce cost and manage high uncertainty as the risk management on the buyer and not a lead vendor who may pass the risk around. Firm fixed-price contracts are ideal when uncertainty is low and places the risk on the contractor. Time and material contracts should be sparingly used but serve well in augment labor situations where the buyer has direct control and oversight of hours.

In the end, the agreements provide the necessary structure promoting a successful procurement management program.

Conclusion

Leveraging complex adaptive systems as the structural underpinning of complexity creates a framework for innovation that solves problems and increases value to the project. Layered on top of the complex adaptive systems framework is a system of agreements that frame the communications, information sharing, and collaboration as well as any other structures necessary for the management of the procurements in complex projects. Actors in the procurement process need adequate guidance to collaborate, share information, and communicate. In the Heathrow Terminal project, the British Airport Authority took on the role of systems integrator rather than allowing the prime contractor or lead supplier to perform this task. In doing so, a strategic supply network was created where the level of innovation had been considered low (Brady, 2011, p. 470). The system of complex adaptive framework, agreements, and the Project Management Institutes project procurement practices can provide the program management levels necessary to reduce cost overruns in complex projects.

References:

Brady, T. (2011). Creating and sustaining a supply network to deliver routine and complex one-off airport infrastructure projects. International Journal of Innovation & Technology Management, 8(3), 469-481.

Defense Systems Management College. (2008). Comparison of major contract types. [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://www.dau.mil/sites/locations/dsmc/default.aspx.

Flemming, Q. (2003). Project procurement management: contracting, subcontracting, teaming. (1st e.d.). FMC Press. California.

Garret, G. (2010). World-class contracting (5th ed.). CCH, inc. USA. Isik, F. (2010). An entropy-based approach for measuring complexity in supply chains. International Journal Of Production Research, 48(12), 3681-3696.

Li, Z., Yanfei, X., & Chaosheng, C. (2009). Understanding the value of project management from a stakeholder's perspective: Case study of mega-project management. Project Management Journal, 40(1), 99-109. doi:10.1002/pmj.20099

Lind, D. (2012). Integrated project delivery for building new airport facilities. Journal Of Airport Management, 6(3), 207-216.

Project Management Institute. (2008). A Guide to the project management body of knowledge (PMBOK Guide). (4th ed.). Newtown Square, PA: PMI.

Surana, A., Kumara, S., Greaves, M., & Raghavan, U. (2005). Supply-chain networks: a complex adaptive systems perspective. International Journal Of Production Research, 43(20), 4235-4265. doi:10.1080/00207540500142274

Yeow, J., & Edler, J. (2012). Innovation procurement as projects. Journal Of Public Procurement, 12(4), 472-504.